|

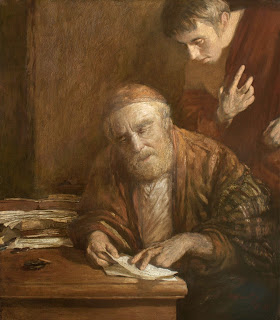

| Parable of the Unjust Steward. 2012. Artist A.N. Mironov [14] |

To begin to explore the parable of the unjust steward, then, is to enter into a world in which none of characters stick to their societally ordained roles and miraculously absurd things happen. This parable is a bit like the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez in which the miraculous has a way of pointing out the absurdity of the original situation. The harsh steward, whose role has been to extract and collect debts from the tenant farmers who worked the land, finds his salvation in sending the money flowing in reverse, back to the people he is usually collecting from. The wealthy landowner, who is furious at the steward for squandering his property, ends up praising that very same steward for losing him even more money. And then there is Jesus who appears to be encouraging profligacy, urging us all to use ‘dishonest wealth’ to make friends for ourselves. This is one of the many instances in the Gospels in which there appears to be a wry sense of humor at work.

There are many different theories and schools of thought as to how we should approach this vexing parable, perhaps more so than any other of Jesus’ parable, so I’m going ahead with my own interpretation knowing this will be profoundly unsatisfying to many (most?). Nevertheless, one approach that I have found compelling comes from Richard Dormandy who encourages readers to take a step back and observe that this parable falls within two other stories of rich men.[1] His insight is that the parable of the unjust steward is the second in a three-part cycle of stories about wealthy men that explore the proper use of wealth.

In what follows, I will dig into the parable of the unjust steward - going character by character, exploring the exploitative dynamics between landowners and their stewards to their tenant farmers and slaves. Ultimately, I will return to Dormandy’s insight that this is part of a larger story about how wealth should be used told in three parts. For, “as Luke writes to Theophilus, the constant question is ‘How should a rich man serve God?’ Or to put it more starkly, how can a rich man enter the Kingdom of God at all?’”[2] Finally, I’ll explore what has become something of a theme in this blog -- namely, a questioning of mainline Christianity’s focus on stewards and stewardship as the main way the Church talks about wealth. The parable of the unjust steward is one of the few places in the Gospels that explicitly mentions the role of a steward - and yet he is only praised when he repents and acts as an anti-steward. How, exactly, the Church has ended up centering its main discussion of wealth on the character of a overseer of slaves and property manager, and has chosen to pass over so many other good examples of how to use wealth in order to praise this exploitative role, is a question that continues to baffle me.

Three Rich Men: A Story About How To Use Wealth

Luke tells three stories of rich men, one after the other, in a collection of materials that is unique to Luke’s Gospel. The three stories, Dormandy argues, are tied together by the themes of profligate mercy and unexpected forgiveness of debts, and together they explore the question of how wealth is supposed to be used.

First, we hear about a rich father who uses his wealth to celebrate the return of his wayward son (the Prodigal Son in Luke 15:11-32). This is immediately followed by the story of the rich landowner and his unjust steward who use wealth to forgive debts (Luke 16:1-13). Six verses of commentary from Jesus follow - including the observation that ‘You cannot serve both God and wealth’ - which set the reader up for the final story of the rich man who dresses in fine clothes, throws feasts for himself, and fails to see the desperation of Lazarus at his gate (Luke 16:19-31). Unlike the prior two stories which center on the forgiveness of both sins and debt, no forgiveness or mercy is shown to the rich man when he dies. For in death, Abraham tells the rich man, “Child, remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony. Besides all this, between you and us a great chasm has been fixed, so that those who might want to pass from here to you cannot do so, and no one can cross from there to us,” (Luke 16.25-26).

Parable of the Prodigal Son

In the Parable of the Prodigal Son, the father is deliberately described as a wealthy landowner who employed many hands (Luke 15.17) and who had property to divide between his two sons (Luke 15.12). The younger of the two sons spends all his inheritance in travel and dissolute living - including on prostitutes, if we are to believe the later accusations of his older brother. When a severe famine befalls the land, this newly poor prodigal son must hire himself out to one of the citizens of that country; he ends up so hungry that he is jealous of the food of the pigs he is tending. “He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything,” (Luke 15.16). He is, in fact, in a similar position to that of Lazarus in that he "longed to satisfy his hunger with what fell from the rich man’s table” (Luke 16.21). It is at this low point that the prodigal son recalls that even his father’s hired hands are given something to eat. He returns to his father, begs for forgiveness, and asks to be treated as one of his father’s hired hands (Luke 15:18-19).

Many of Jesus’ parables hinge on an unexpected turn and the parable of the prodigal son is no exception. Instead of a stern rejection of the prodigal son’s return, the father welcomes his son back with open arms and - significantly - wastes even more wealth celebrating his return. The father’s incautious generosity is both striking and disturbing. Having already given his youngest son half of his property, he now gives his returned son a ring for his finger, sandals for his feet, and orders a fatted calf to be killed for a feast, “for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!” (Luke 15.24).

It is only at this point that the main question - and conflict - in the parable appears, for then the dutiful older brother steps forward and bitterly complains about his father’s imprudent generosity. “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!” (Luke 15.29-30). Is the rich father’s forgiveness, many gifts, and throwing of a feast for his wayward son incautious, irresponsible, and perhaps even immoral? The parable concludes with the father telling his dutiful and responsible son, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found,” (Luke 15.31-32).

The Parable of the Prodigal Son ends up affirming the father’s wasteful - and possibly even immoral - generosity toward the wayward son. If stewardship is about prudent management of resources, Jesus turns prudency on its head by making the dutiful and responsible son the antagonist of the story, and the irresponsibly generous father the hero. Dormandy notes that the landowner “earns the disapproval of his firstborn firstly, for giving half his wealth away to the prodigal younger brother, and then for wasting even more on the boy when he returns home. This sets us up for the Parable of the Steward, which itself raises the question of ‘what is waste?’ ‘How should wealth be used?’ and ‘How do we make right judgments?’[3]

The Parable of the Unjust Steward

The second story in this cycle of three is that of the Unjust Steward, which like the Prodigal Son, explores themes of the search for a safe home, forgiveness (in this case, forgiveness of debts), and concludes by praising incautious, irresponsible, and even immoral generosity.

Jesus’ story begins by talking about “a rich man” who hears that his steward was squandering his property (Luke 16.1). Right off the bat, then, we know that this is a story about riches, wealth, and especially the misuse of wealth. This rich man demands the steward give an account of his management but then, in anger, fires the steward before any such account could be given (Luke 16.2). The steward is shocked and afraid. He finds himself at a low point, in a similar situation to the prodigal son who squandered the property entrusted to him. The steward asks himself, “What will I do, now that my master is taking the position away from me? I am not strong enough to dig, and I am ashamed to beg,” (Luke 16.3). Like the prodigal son, he must now come up with a plan to find a safe home.

Further, there is evidence that the steward's attempts to find a safe home would have been a return journey of sorts. It is important to note that the steward was oftentimes a born a slave in the master's household. As a steward, he would have been "first slave" or his master would have made him a freedman in order to serve in this role.[4] Stewards occupied a uniquely precarious - and much-hated role - in the exploitative hierarchy of the Roman estate in that his considerable authority as property manager depended on his ability to render regular profits for his master from the labor of tenant farmworkers and slaves. Trying to find a safe home after his dismissal would have meant returning to the very people he came from and whom he'd actively managed.

This begins to give us insight into the world of tenant farming, something which is critical to understanding the significance of the parable. "Inasmuch as agriculture served as the backbone of the ancient economy, tenant farming came to be a widely implemented system of estate management by absentee landowners and indeed the preferred method during the early empire,” writes John Goodrich about the parable of the unjust steward.[5] In the lead up to the first century, a growing number of tenant farmers faced the bitter task of working the very land they once owned, having been pushed by increasing tithes, taxes, and other socioeconomic pressures, into selling their ancestral lands and now sending surpluses to the landowner who lived in urban areas.[6] In Bruce Longnecker’s Remember the Poor, we catch a glimpse of the steward’s unique role when he describes how a significant number of landless people in the first century were tenant farmers renting their land "from 'absentee landlords' (often at exorbitant cost and for short periods of time), or were slave-tenants tasked with the responsibility of extracting the yields of the land for the landowner."[7] On the plight of the tenant farmers who we read about in the unjust steward, Goodrich writes:

Of course there are examples of tenants making large profits from their agricultural yields, but the vast majority of tenant farmers barely managed to meet subsistence. If rent was high and the harvest poor, a tenant could be left without adequate funds to pay rent or even to sow one’s field for the ensuing year. The acquisition of debt by both small-and large-scale tenant farmers was therefore very common and the consequences of defaulting were often quite severe.[8]

The steward played an important role in this arrangement on behalf of the landowner insomuch as he served he held a “representative nature” and was “able to manage the principal’s many financial responsibilities just as if the owner were present, since the principal’s confirmation accompanied the financial decisions made by the administrator.”[9] It was well within the steward's power to increase or reduce debts, though the typical response to debt-holders was strikingly harsh. “In addition to expulsion from an estate, there were three courses of legal action that landlords could take against their debtors: property confiscation, imprisonment, and debt bondage (Matt 18:23-24; cf. Matt 5:25-26//Luke 12:58-59)...Many extant leasing contracts from early Roman Egypt in fact contain declaration clauses indicating not only that a steep interest rate would be added to all late payments (e.g., 50 percent), but also that the landlord would have the right to take action against both the tenant’s person and property should the lessee continue to default.”[10] Normally the steward joined his master in ratcheting up the pressure on the tenant landowners who were indebted.

When we hear the steward, then, desperately wondering what he will do now that he no longer has his master’s support, recognizing that he isn’t strong enough to dig, we should bear in mind that among the first hearers of this parable were those on the underside of this exploitative arrangement, including tenant farmers and slaves. They may have smiled with more than a hint of revenge, at the prospect of an oppressive steward having to return to the very people and situation he formerly lorded over.

The decision he makes, then, is a return journey of sorts, one made in order to try to find a safe home for himself for the time after the news of his dismissal reaches his estate. In an act of anti-stewardship, the steward begins to summon his master’s debtors to release them from their debts. Speaking to a debtor who owed a hundred jugs of oil, the steward tells him, “Take your bill, sit down quickly, and make it fifty.” To another who owed wheat, “Take your bill and make it eighty.”

Bruce Longnecker observes that “the size of the debts involved is extraordinary”, so large that “they may be the debts of an entire village.”[11] The amounts would have been immediately comprehensible to the first hearers of this parable, and so these are details told to convey the extraordinarily exploitative situation that the landowner and steward had been oppressing the farmers and slaves with, as well as to signify the relief that would have been felt among the debt-holders by this highly unusual, theologically significant action.

I say that it is theologically significant because the act of releasing debtors from oppressive debt has profound significance in scripture as a sign of God’s liberative action at work. In Leviticus 25:35-38, the economic slavery of debt is connected with the slavery experienced by the Hebrew people in Egypt: “If any of your kin fall into difficulty and become dependent on you, you shall support them; they shall live with you as though resident aliens. Do not take interest in advance or otherwise make a profit from them, but fear your God; let them live with you. You shall not lend them your money at interest taken in advance, or provide them food at a profit. I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, to give you the land of Canaan, to be your God.” To release the poor from the economic slavery of debt is part of Jesus’ proclamation that he has come to bring Good News to the poor in Luke 4:18a.

But the strangeness of this parable does not end here for we learn that “his master commended his dishonest manager because he had acted shrewdly.” The miraculous turn that takes place next is a reminder of how part of the power of parables lies in their ability to surprise - even scandalize - listeners. In this case, the surprise commendation of the master sets up Jesus’ observation that “the children of this age are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light,” and his counsel to “make friends for yourself by means of dishonest wealth so that when it is gone, they may welcome you into the eternal homes,” (Luke 16.8-9). Like the parable of the prodigal son, the point may be that wealth - including even the dishonest wealth of an exploitative landowner - is intended to be used, though in this case Jesus urges wealth to be applied toward the merciful remission of debt and the freeing of the poor from economic slavery.

Jesus concludes by commending the steward for knowing what to do with dishonest wealth and therefore knowing who is the true master he should be serving: “If then you have not been faithful with the dishonest wealth, who will entrust to you the true riches? And if you have not been faithful with what belongs to another, who will give you what is your own? No slave can serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth,’ (Luke 16.11-13). It is better to serve God rather than wealth, and to use even dishonest wealth for godly purposes.

Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus

Whereas the first two parables explore how wealth is to be used, the final parable - that of the Rich Man and Lazarus - is a warning about what awaits rich men who fail to use their dishonest wealth appropriately. First, we gather that the rich man uses his wealth solely for himself. Jesus describes him as one “dressed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day,” (Luke 16.19). Unlike the father of the prodigal son, these feasts and finery are for a party of one, and there is no celebrating with the deserving or undeserving poor. Indeed, amidst his feasting he completely fails to see the poor man, Lazarus, languishing at his gate who “longed to satisfy his hunger with what fell from the rich man’s table.”

In death, however, God’s justice results in a reversal of their fates and it is the rich man who is tormented and now languishing. Significantly, it is now the rich man who joins the prodigal son and unjust steward in experiencing a low point, and in having his fate determined by an act of mercy. But in this case alone, no mercy is given. Abraham responds to the rich man’s request for mercy - a forgiveness of what is rightfully owed - by saying that it is too late, that the great chasm has been fixed (Luke 16.25-26). Abraham retorts that the rich man and his brothers had Moses and the prophets warning them to act differently in their lifetimes, yet they chose to ignore such warnings while they were alive, and now it is much too late.

An Aside about Stewards and Stewardship

I’ll conclude this exploration of the parable of the unjust steward with a short aside about mainline Christianity’s focus on the personality and function of the harsh but effective steward as the primary way of talking about Christians’ relationship to wealth. When we seek to be “good stewards” and even dedicate an entire “stewardship season”, what exactly are we praising?

I truly do not know at what point Christianity - or at least mainline Protestantism - began focusing its discussion of faith and wealth on the character of the steward. My guess, at this moment, is that this is connected to the emergence of parishes and tithing practices in the tenth century. Diarmaid McCullough notes: “As parishes were organized, it became apparent that there were new sources of wealth for churchmen as well as for secular landlords. The parish system covering the countryside gave the Church the chance to tax the new farming resources of Europe by demanding from its farmer-parishioners a scriptural tenth of agricultural produce, the tithe. Tithe was provided by many more of the laity than the old aristocratic elite, and was another incentive for extending the Church’s pastoral concern much more widely.”[12]

It is in this parish context, one in which the tithe emerged as a tax on the laity, that the role of the steward begins to make a disturbing kind of sense. Suddenly the bishop/lord becomes the absentee landlord; the parish is the estate; the steward serves to collect the tithe/debts on the Lord’s behalf; and it is still the tenant farmers and slaves on whose work and resources the entire system relies. It seems to me that “faithful stewardship” may have emerged as the theological justification for this parish/tithing arrangement.

It is certainly a historic model - though then again, so too is slavery - and it’s worthwhile recalling here that in the parable of the unjust steward, the steward is only praised when he repents and begins acting as an anti-steward, releasing people from debt. Jesus' praise comes when the money flows out, not in. Indeed, over and over, Jesus’ message on wealth is oftentimes the exact opposite of what is praised as sound stewardship practices in that he urges incautious, irresponsible, and seemingly even immoral acts of generosity and mercy.

For when we focus on the steward, we ignore many other figures in the Gospels who can provide a much more thoughtful and interesting discussion about how wealth is supposed to be used. In addition to the stories of the three rich men detailed above (the parable of the prodigal son, that of the unjust steward, and the rich man and Lazarus), in the Gospel of Luke alone, there are the stories of:

- The parable of the Good Samaritan, who used his wealth to care for a stranger despite inconvenience and even danger to himself (Luke 10.25-37)

- Jesus’ parable of the rich fool who builds larger and larger barns to store his growing amount of grain and possessions. But he can't take all that wealth when he dies! Luke 12:13-21

- Jesus’ telling the rich man to “Sell your possessions, and give alms. Make purses for yourselves that do not wear out, an unfailing treasure in heaven, where no thief comes near and no moth destroys. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” Luke 12.33-34

- Jesus’ parable of the Great Banquet, in which a frustrated rich man eventually throws open the doors to invite “the poor, the maimed, the blind and the lame” Luke 14:15-24

- Jesus’ words to the rich ruler who asks Jesus what he must do to earn eternal life. “Sell all that you own and distribute the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.’” Luke 18.18-30.

- Zacchaeus who said to Jesus, “ ‘Look, half of my possessions, Lord, I will give to the poor; and if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I will pay back four times as much.’ Luke 19:8-9[13]

Any of these characters and stories would be a far better focus - and far more faithful representation of the Gospel’s message on wealth - than the harsh and effective steward who manages property and goes about collecting debts from tenant farmers and slaves on behalf of an absentee landowner. September Stewardship Season makes as much sense to me as Overseer October, Middle-Management March, and Debt-Collector December. What were we thinking? Ironically, it is we, in fact, who have been unjust stewards of the Gospels' surprising messages around faith and wealth.

What is wealth for?

Through the parables of these three rich men, a few themes emerge about how wealth should be used. Wealth - including wealth gained by unjust means - is supposed to be used in the here and now; there is no use waiting to use riches until after one’s death. This idea is also supported by the parable of the rich fool who Jesus condemns for simply storing up his wealth in larger and larger barns (Luke 12.13-21).

But if we are to use wealth in the here and now, it must be for something more than just purple cloth, fine linen, and feasting with our inner circle alone. Like the father of the prodigal son, we are to use our wealth in irresponsible acts of generosity and mercy, holding ‘great banquets’ with saints and sinners, the dutiful and the prodigal, and for banquets in which ‘the poor, the maimed, the blind and the lame’ are invited.

In the parable of the unjust steward, we are advised to use dishonest wealth for the merciful remission of debt and the freeing of the poor from economic slavery. This theme is picked up in the person of Zaccheus who is granted salvation when he gives half his possessions to the poor and pays those he has defrauded back four times as much.

Finally, in the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, Jesus offers a warning to those who retain such wealth only for themselves and their kin -- namely, that God’s great reversal awaits if we do not change our ways. The wealthy have the opportunity to demonstrate irresponsible acts of generosity, mercy, and the forgiveness of debts. No such acts of mercy await us if we fail to do so in this lifetime.

________________

[1] Dormandy, Richard. “UNJUST STEWARD OR CONVERTED MASTER?” Revue Biblique (1946-), vol. 109, no. 4, 2002, pp. 512–527. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44092120. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021.

[2] Dormandy, Richard. “UNJUST STEWARD OR CONVERTED MASTER?” Revue Biblique (1946-), vol. 109, no. 4, 2002, pp. 512–527. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44092120. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021. Page 514

[3] Dormandy, Richard. “UNJUST STEWARD OR CONVERTED MASTER?” Revue Biblique (1946-), vol. 109, no. 4, 2002, pp. 512–527. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44092120. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021. Page 514

[4] Malina and Rohrbaugh, Social Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels, Page 292

[5] GOODRICH, JOHN K. “Voluntary Debt Remission and the Parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1—13).” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 131, no. 3, 2012, pp. 547–566. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23488254. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021. Page 553

[6] Longnecker, Bruce. Remember the Poor. Page 24-25

[7] Longnecker, Bruce. Remember the Poor. Page 23.

[8] GOODRICH, JOHN K. “Voluntary Debt Remission and the Parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1—13).” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 131, no. 3, 2012, pp. 547–566. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23488254. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021. Page 554

[9] GOODRICH, JOHN K. “Voluntary Debt Remission and the Parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1—13).” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 131, no. 3, 2012, pp. 547–566. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23488254. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021

[10] GOODRICH, JOHN K. “Voluntary Debt Remission and the Parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1—13).” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 131, no. 3, 2012, pp. 547–566. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23488254. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021. Page 554

[11] Malina and Rohrbaugh, Social Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels, Page 292

[12] Mcullough, Diarmaid. Christianity: The First Three Thousand years. Page 369

[13] This list of references to wealth in the Gospel of Luke is adapted from Longenecker, Bruce. Remember the Poor. Page 124

[14] Andrey Mironov, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Comments

Post a Comment